Trumped out: You Don’t Get to Vote Here

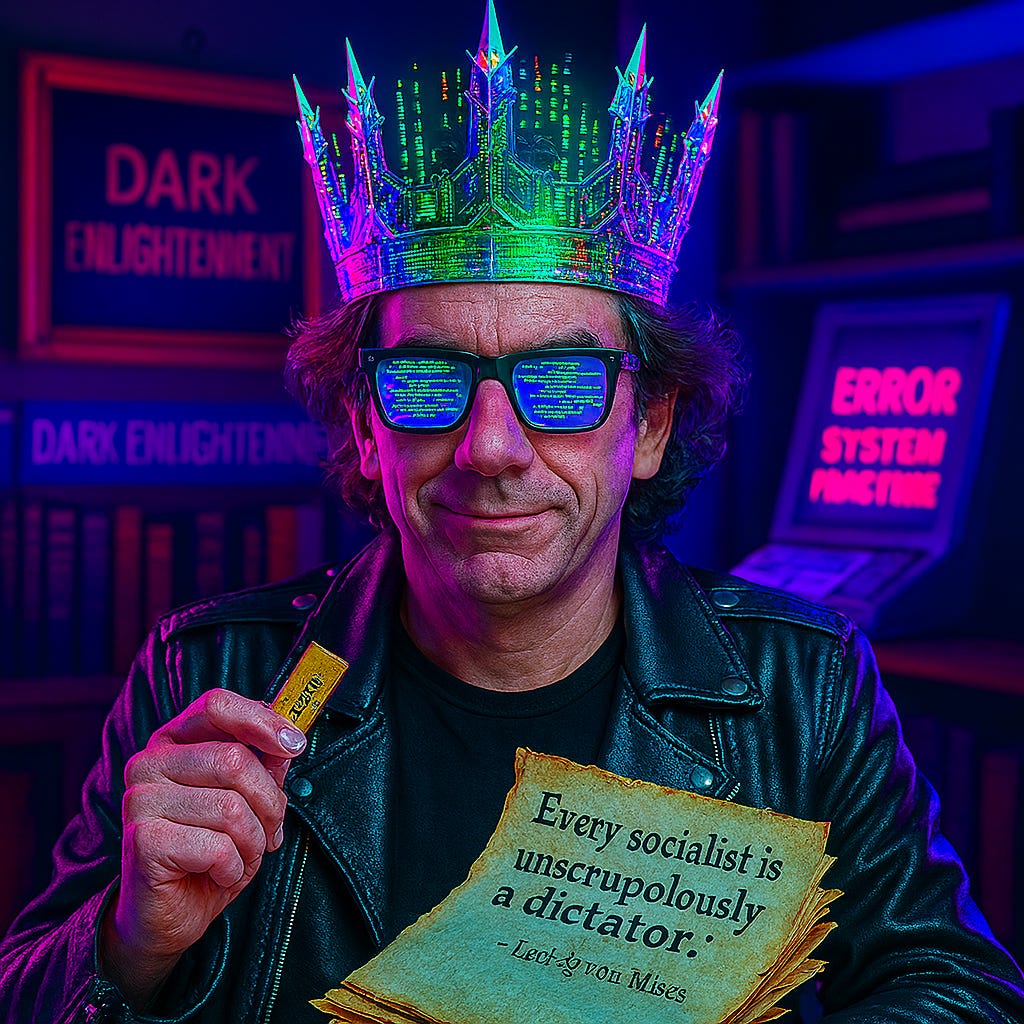

Curtis Yarvin’s blueprint for monarchy, merit, and mass submission.

Curtis Yarvin’s Kingdom of One: An Introduction to “The CEO Kingmaker

In another life, Curtis Yarvin might have stayed a niche software engineer with a fondness for Borges, obscure programming languages, and the contrarian thrill of arguing against conventional wisdom in forgotten corners of the internet. Instead, he became something stranger: a man who built an ideology out of disillusionment, and offered it—half in jest, half in blueprint—as a cure for the modern world.

You might picture him as a crank in a basement, but the truth is more dangerous: his words now whisper through Senate offices and Silicon Valley boardrooms, a manifesto masquerading as a blog. He is neither a madman nor a mastermind, neither harmless nor wholly persuasive. He is, like many men who think they see through everything, mostly looking in the mirror.

Yarvin’s personal story reads like a Bildungsroman for the hyper-verbal outcast. A child prodigy turned polymath dropout, he cycled through elite institutions without ever quite fitting in, gathering resentment like lint. By his own account, he was “too smart” for democracy before he was old enough to vote. His enemies were mediocrity, consensus, and moral certainty. His solution? Strip power from the people and hand it to a sovereign who knows better. Someone efficient. Like a CEO. Like him.

This piece is not a work of fandom. It is an autopsy.

Curtis Yarvin was born in 1973 into an American contradiction: Jewish communist grandparents on one side, old-line Protestant stock on the other. His father, Herbert, a disillusioned philosopher turned reluctant diplomat, carted the family from post to post—Cyprus, the Dominican Republic—representing a government neither he nor his son much trusted. Curtis absorbed the cynicism early. Years later, he'd suggest shuttering U.S. embassies altogether—pointless outposts, he claimed, of a dying empire.

Socially, Curtis was a misfit from the start. Homeschooled for stretches by his mother, he skipped three grades and was reading advanced philosophy while his peers were learning fractions. When the family settled in Columbia, Maryland in 1985, twelve-year-old Curtis enrolled in public high school as a sophomore. It didn’t go well.

He wasn't a cute prodigy; he was strange. Awkward. Off-putting. He remembers being seen not as smart, but as threatening. His classmates called him “Helmet Head”—not just for the bike helmet he insisted on wearing indoors, but for the stubborn impermeability of his mind. One student joked that the helmet must be to keep new ideas out.

PART I: The Boy Who Would Be King

Curtis Yarvin spent his early life in diplomatic drift. His father, Herbert, was a brilliant but thwarted academic—an American philosopher who couldn’t find his place in academia and instead ended up stationed in foreign service posts he quietly loathed. The family pinballed across embassies and postings, most notably in the Dominican Republic and Cyprus, the kind of places that feel both cosmopolitan and lonely for a bookish child. Curtis was neither rooted nor at home. He didn’t learn about the local cultures; he didn’t make close friends. He read.

This was not a sunny, curious kind of precocity. He wasn’t charming. He was odd. The kind of child who corrected adults, who stared too long, who remembered every fact and forgot every face. His mother homeschooled him intermittently—not for religious reasons, but because the classroom couldn’t hold him. By the time he was ten, he was devouring obscure philosophy texts online and pulling apart world systems in the margins of his notebooks. Notebooks, he rarely let anyone read.

The household itself was strange. Ideologically fractured. His paternal grandparents had been Jewish communists, proud of their radicalism. His mother’s side was old New England Protestant, educated and reserved. That collision, revolutionary fire and patrician cold ran through the boy. Add to this the simmering discontent of a highly intelligent father who believed himself underutilised by the world, and you begin to see the emotional atmosphere that shaped Curtis: intellectually intense, affectionately muted, and vaguely embattled.

There’s no indication that Curtis was abused. But there’s every sign that he was profoundly unseen, except by himself.

When the family moved back to the United States in 1985, 12-year-old Curtis enrolled at a public high school in Columbia, Maryland, as a sophomore. He had skipped three grades. That fact alone would have made him a target. But it was more than age. He didn’t talk like the other kids. He didn’t walk like them. His jokes didn’t land, and his arrogance wasn’t masked by charm. He wore a bicycle helmet indoors. Not for a medical reason. Just because. The nickname — Helmet Head— came fast. So did the isolation.

Teachers didn’t know what to do with him. They recognised the intelligence. But they also saw something brittle, something oppositional—not rebellious in a teenage way, but oppositional like a man waiting for the world to fail so he could say “I told you so.” One teacher recalled he often seemed “elsewhere”, reading when others were talking, writing code in the back of the room, or interrupting class with questions that felt like traps. A quiz wasn’t something to pass; it was something to disprove.

His peers were even less forgiving. Some found him scary, others simply annoying. A few, according to Yarvin himself, thought he was a “weird, threatening, disturbing alien.” He wasn’t bullied so much as ignored, and he returned the favour by withdrawing into the fortress of his intellect. If you asked him how he was doing, he’d likely respond with a reference to Joseph de Maistre or Carlyle, not as a joke, but because that’s where his brain lived. He was, in every sense, out of sync.

Yet he wasn’t friendless. At fifteen, he was selected for Johns Hopkins University’s elite Study of Mathematically Precocious Youth—a program for kids whose IQ scores weren’t just high, but warping. There, at least, he wasn’t the smartest person in the room. But even among the gifted, Curtis stood out. He wasn’t interested in just solving problems; he wanted to rewrite the rules that made the problems possible.

His appearance didn’t help. Pale, intense, frizzy-haired, with a stare that was half asleep and half challenge, he looked less like a teenager than like a very young professor in the middle of a nervous breakdown. Photos from that time show a thin, haunted boy, with a closed-lipped expression and eyes that seemed to be asking: Why am I here? It’s unclear whether he meant the school, the town, or the planet.

Still, for all his alienation, he wasn’t a nihilist. Not yet. He wanted structure. He wanted logic. He wanted to make sense of a world that felt impossibly irrational, especially when it came to how people related to each other. He began to develop what would later become his obsession with order. Not kindness. Not love. Not justice. Order. As if he could swap the chaos of high school cafeterias and foreign embassies for a cleaner system, one ruled by intellect and efficiency, not popularity or emotion.

At Brown University, which he entered not long after most kids take the PSAT, he tried to fit in. But his intensity, again, kept him apart. He gravitated to debate, to argument, to dense theory over social bonding. He wasn't a shut-in, but neither was he socially fluid. Former girlfriends would later describe him as “hippie adjacent” during this period. He wore a ponytail, sported a silver earring, dropped acid, and even showed flashes of political liberalism. But the softness never stuck. The performance of empathy was never as convincing as the performance of intellect.

He graduated at 18 and went on to UC Berkeley for graduate work in computer science. But that, too, collapsed. He didn’t like being taught. Didn’t like being corrected. And he especially didn’t like having to wait for slow minds to catch up. He left after a year and a half, unimpressed.

By then, the damage was done. Not just to his trust in institutions, but to any belief that a world designed by others could ever make sense. Curtis Yarvin didn’t want to be part of a system.

He wanted to replace it, not with revolution, but with a slow rewrite of the code. A project so insidious, it would take a decade for Washington to notice the malware in its machinery.

PART II: The Mind in Exile

Curtis Yarvin left Berkeley with no degree, no allies, and no faith left in institutions. He had entered the graduate program in computer science with the same confidence that marked his childhood — a belief that he was the smartest person in any room, and that the system would catch up eventually. It didn’t. Professors found him argumentative. Peers found him rigid. He left after eighteen months.

But it wasn’t a failure. It was reinforcement. Another failed institution. Another room that couldn't handle him. It confirmed what he already suspected: the world wasn’t broken, it was designed badly. And it needed someone like him to redesign it.

In the Bay Area, during the first tech boom, that belief wasn’t unusual. What made Yarvin different was that he didn’t want to disrupt the market — he wanted to replace the state.

He got his start at a small mobile web startup called Libris, which became Phone.com. He was good at what he did: code, system architecture, low-level precision thinking. When the company went public, Yarvin walked away with around a million dollars. He didn’t spend it. He didn’t chase status. He retreated into thought, into theory, into control.

This was the moment most people lean into power or peace. Yarvin chose neither. He chose exile.

While still working freelance as a programmer, he began a second, deeper project: reading history like it was a source code problem. Not for inspiration. For flaws. He used early Google Books to dig through political philosophy like a hacker scanning legacy software. And what he found disturbed him — not because it was false, but because he believed it was more true than anything being taught.

He started with libertarians — Rothbard, von Mises, Hayek — drawn to their anti-state realism. But even they didn’t go far enough. Libertarianism, to him, was infected with a childish faith in consensus. He wanted authority. Stability. Design.

The real breakthrough came with Hans-Hermann Hoppe’s Democracy: The God That Failed. Hoppe argued that monarchy was superior to democracy because it treated the state like private property. A king had a long-term incentive not to ruin his country. A president, like a renter, just extracted what he could. Yarvin didn’t just agree — he saw a blueprint.

Then came Thomas Carlyle — the 19th-century English reactionary who mocked democracy as mob rule and romanticised strong, moral rulers. Carlyle gave Yarvin not just a logic for hierarchy, but a tone. Irony, scorn, absolutism. It was a language he already spoke fluently.

Next was James Burnham, who insisted all governments were run by elites, regardless of whether they called themselves democracies or dictatorships. That clinched it. The people never ruled. They never had. What mattered was not “freedom,” but who controlled the machinery, and whether they were competent.

This wasn’t philosophy anymore. This was the diagnosis.

By the early 2000s, Yarvin was living in San Francisco, quietly constructing what he would later call his “ideology.” It was slow, obsessive, and personal. While other tech types chased IPOs, he built a parallel mental universe: one in which America had failed not because of policy, but because of structure. The system itself was illegitimate.

He called it “the Cathedral.” His term for the vast, decentralised web of media, academia, and bureaucracy that — in his view — acted as an unofficial ruling class. Not through conspiracy, but through consensus. Progressivism, he believed, had become the modern world’s state religion, enforced not with police, but with prestige.

At night, he read. During the day, he worked on Urbit, a decentralised software system he envisioned as the technical version of this political project: a way to build a new internet, with new rules, outside the current regime. It was his first “exit architecture.” A place for people like him.

That isolation was interrupted — briefly, meaningfully — by love. In 2001, Yarvin met Jennifer Kollmer, a playwright, via a Craigslist ad. They married. Had two children. She was his opposite in many ways: emotionally present, artistically curious, socially generous. She grounded him. Their life was quiet, strange, full of books and contradictions.

But the worldview continued to harden. And even then, he wasn’t writing publicly. Not yet.

So why did he start blogging?

Because eventually, the diagnosis demanded a prescription.

By 2004, Yarvin had come to believe that the modern world was living a lie — and that no existing ideology, left or right, could describe it truthfully. He believed history was the story of decay masked as progress. He believed liberalism was a confidence trick. And above all, he believed that only a single, competent sovereign — like a CEO — could bring order to chaos.

But no one was saying this. Not in the way he wanted it said. Not with rigour, venom, precision.

And so he built a pseudonym — Mencius Moldbug — as both disguise and persona. A voice that could be playful, brutal, and unrelenting. Not because he was hiding, but because he wanted to strip truth of its social cost. The blog became a testing ground for theory. A recruitment tool for elites. And a sword swung at democracy from the safety of a laptop.

Unqualified Reservations launched in 2007. But in truth, it had begun years earlier — in a teenager’s alienation, in a dropout’s bitterness, in the late-night footnotes of dead men who hated the crowd.

It wasn’t just a blog.

It was a manifesto in waiting.

PART III: The Rise of Moldbug

By 2007, the mask was ready.

Curtis Yarvin had spent the past five years assembling a worldview out of fragments—Hoppe’s property-state monarchism, Carlyle’s hero-worshipping elitism, Burnham’s cynical power realism. But Yarvin didn’t just want to write an essay. He wanted to find a worldview. Not for the public. For the few. The smart. The alienated. The strategically placed.

He knew he couldn’t do that as Curtis Yarvin, libertarian ex-programmer and fringe philosopher in a grief-shadowed San Francisco apartment. He needed distance. A voice that could be stylised, elevated, and cruel. Something with texture and plausible deniability.

So he invented one.

Mencius Moldbug.

A name that felt ancient and parodic at once. Mencius, the Confucian sage; “Moldbug,” the Poe-like image of rot and infestation. It wasn’t subtle. That was the point.

The blog he launched under that name—Unqualified Reservations—was neither slick nor readable in the usual sense. The posts were sprawling, pedantic, and deliberately difficult. Sentences unspooled for pages. Footnotes nested like Russian dolls. There were jokes, yes, but they were layered under theory, sarcasm, and contempt. The style wasn’t populist. It was testing you. It was gatekeeping by design.

What you found, if you stayed, was a radical proposition: democracy is not just flawed, it’s illegitimate. America, Moldbug claimed, was not a republic but a decaying theocracy run by a class of secular priests: journalists, professors, HR departments. He called this elite consensus machine “The Cathedral”, a term that has since infected the vocabulary of the online right.

The Cathedral didn’t need to coordinate. It didn’t need a central office. It simply reproduced itself: Harvard trained the Times, the Times legitimised the White House, and the White House subsidised Harvard. Circular, invisible, omnipresent. It was Yarvin’s total theory of elite control, disguised as democracy.

And then came the real pitch:

Stop pretending you have power.

Withdraw. Disengage. Let the system collapse. Then rebuild it—not with ballots, but with architecture.

He called it “formalism”—the idea that power should be held by those who actually wield it, and that this fact should be openly acknowledged. No more illusions of people's power. No more elections. Just a single executive, chosen for competence, ruling absolutely—like a CEO. Like a monarch. Like a sovereign running a nation, the way one runs a company.

This wasn’t just nostalgia for kings. It was a design brief for post-democracy. A corporate monarchy. A SovCorp: sovereign corporation.

Moldbug didn’t write to convert the masses. He wrote to the seed elites. He wanted people in tech, in finance, in law, in government, to read his blog in private and begin to doubt what they’d been taught. To see democracy not as sacred, but as inefficient. Ugly. Weak. And worst of all, mediocre.

And it started working.

Links to Moldbug’s blog began circulating on mailing lists in Silicon Valley. Among engineers. Venture capitalists. Quietly, through the backchannels of the libertarian-to-accelerationist pipeline, the Cathedral theory caught fire. A young Peter Thiel was reportedly an early reader. So was Patri Friedman. So was Balaji Srinivasan.

By 2008, Yarvin’s posts were being passed around as contraband thought. Dangerous ideas for smart people who were bored with being polite. He published a 120,000-word treatise titled “An Open Letter to Open-Minded Progressives,” designed to dismantle every core tenet of modern liberalism, slowly, carefully, with controlled condescension.

This wasn’t just provocative. It was a radicalisation pipeline, engineered to addict a certain kind of mind to the fantasy of unaccountable power. Smart, frustrated, male. The type who had read Ayn Rand at fifteen, Hayek at seventeen, and was now wondering why everything still felt broken. Moldbug offered a clear answer:

Democracy is the problem.

Elites already rule.

Let them.

This was post-political politics. No campaigns. No coalitions. Just a complete redesign. A cold, CEO-style reboot.

Yarvin later claimed he only wrote the blog “to see if it was possible to found a new ideology from scratch.” That statement is both absurd and true. The absurdity is part of the armour. It lets him retreat when challenged—I was only experimenting. But the consistency, the rigour, the scale, none of it reads as casual.

Moldbug wasn’t a game. It was the beginning of a political theology, one that would escape its comment-section cradle to infect policymakers who mistook irony for instruction.

And in the coming years, it would reach far beyond comment sections and into the corridors of power.

PART IV: The Spread

Unqualified Reservations never went viral. It metastasised.

Curtis Yarvin wasn’t aiming for likes, shares, or mass appeal. He aimed for something more durable: penetration into the class that makes decisions. His blog was a slow weapon, calibrated for elite attention spans: obsessive coders, cynical investors, overeducated men with too much time and not enough meaning.

And it worked.

By the early 2010s, Moldbug had become a kind of open secret in Silicon Valley, a philosopher for those who thought they were too rational for politics, too smart for democracy, and too important to wait for reform. His blog was passed around in private Slack channels and lunch meetings. A PDF of “An Open Letter to Open-Minded Progressives” circulated like samizdat.

The appeal wasn’t just ideological. It was stylistic. Yarvin spoke their language: systems, architecture, permissioning, efficiency. He diagnosed liberal democracy the way a software engineer might diagnose a legacy app: bloated, insecure, impossible to patch. Time for a clean install.

Peter Thiel, the billionaire who famously declared, “I no longer believe that freedom and democracy are compatible,” was reading Moldbug. He had already seeded Yarvin’s startup Tlön, which developed the Urbit software platform, Yarvin’s dream of a decentralised digital order, uncorrupted by legacy governance. Thiel didn’t just fund it. He understood it. Urbit was neocameralism in code.

Others followed. J.D. Vance, future senator and Trump’s vice president-elect, began openly echoing Yarvin’s core arguments by the early 2020s: that the administrative state should be purged, that mid-level bureaucrats should be fired en masse, that court rulings could be ignored by a sufficiently strong executive. For all his grand designs, Yarvin's own 'exit architecture'—Urbit—remains a digital ghost town, its promised revolution reduced to a niche tool for crypto enthusiasts. COVID, meanwhile, exposed his 'sovereign competence' as fantasy: the CEOs he idolised begged for bailouts, while governments (flawed as they were) delivered vaccines. Vance wasn't just quoting Yarvin. He was translating him for political use.

And still, Yarvin claimed not to be “doing politics.” His pose was above it all: theory, critique, exit. But the language he developed, “The Cathedral,” “formalism,” “sovereign corporations,” “RAGE” (Retire All Government Employees), was already bleeding into speeches, manifestos, and podcast monologues.

In 2016, Steve Bannon reportedly opened a line of communication with Yarvin. The Atlantic ran headlines calling him Trump’s secret philosopher. He denied being an adviser, but it didn’t matter. The ideas were already in circulation.

They didn’t need Yarvin’s name attached.

They just needed his framing.

Meanwhile, a younger generation of internet reactionaries began citing Moldbug as foundational. Bronze Age Pervert, the pseudonymous author of Bronze Age Mindset, styled himself as a Nietzschean bodybuilder but borrowed liberally from Yarvin’s playbook: contempt for democracy, celebration of hierarchy, and rhetorical style laced with irony and rage.

Yarvin, for his part, treated BAP like a spiritual successor. He even gifted BAP’s book to Michael Anton, a former Trump official and author of The Flight 93 Election, one of the most influential essays of the MAGA era. That moment—Moldbug → BAP → Anton → Trump’s White House—tells you everything about how far the infection had spread.

This wasn’t a movement. It was a memeplex for elites.

And its core message was brutally simple:

You can either rule well or be ruled badly.

Stop pretending democracy is neutral.

Seize the codebase and rewrite it.

Yarvin himself re-emerged publicly in 2020 with a new Substack, Gray Mirror. He dropped the Moldbug mask but not the mission. He appeared on podcasts with right-wing influencers, accelerationists, and institutional contrarians. His tone was more conversational, but the content hadn’t changed.

In one 2020 essay, written before COVID had shut down the U.S., Yarvin calmly predicted the pandemic would expose the American state as “too incompetent to matter.” His proposed solution? Not better public health. A competent sovereign. Always.

The timing couldn’t have been better.

The Trump era had already revealed the limits of procedural liberalism.

Yarvin’s solution wasn’t to fix the machine.

It was to smash it and start again, with someone in charge.

Someone like Musk. Or Thiel. Or, yes, Trump himself, stripped of pretence and unleashed.

By the end of 2024, Trump’s second-term team was openly populated with Yarvin readers. Vance. Anton. Think-tank creatures from Claremont and Heritage whispering about restructuring the federal government. The language of corporate monarchy was suddenly not theoretical.

It was policy planning.

The pseudonym had become irrelevant. The influence was real.

PART V: The Blueprint.

Curtis Yarvin doesn’t just hate democracy.

He wants to replace it. Completely. Cleanly. No halfway reforms, no populist patch jobs. His solution is radical, technical, and profoundly anti-human. And he presents it as the only rational option left.

He calls it “formalism” — the belief that power should be held by those who already wield it, openly and efficiently, without pretence. No more illusions of representation. No more symbolic elections. Just a sovereign with undisputed authority, running the state like a CEO runs a firm.

This is the blueprint.

At its heart lies a single goal: order above all else. Not freedom. Not justice. Not the messy self-correcting friction of pluralism. Just order, streamlined, unopposed, amoral.

And to sell this as a vision rather than a nightmare, Yarvin gave it a name:

The Dark Enlightenment.

Coined by philosopher-turned-reactionary Nick Land, the term was meant to evoke a post-liberal realism, a kind of anti-Kantian Enlightenment for men who saw through the egalitarian lie. But in Yarvin’s hands, the phrase became branding. A posture. A wink to the smart, angry, over-it-all crowd. You’ve read Voltaire? Try de Maistre. You like Mill? Meet Carlyle. You want to save the West? Start by burning the ballot box.

The “darkness” of the Dark Enlightenment isn’t moral ambiguity. It’s ideological clarity:

Hierarchy is natural.

Democracy is fake.

Progress is a lie.

Wrapped in irony and footnotes, it flatters the reader by letting him feel rebellious for siding with power. It doesn’t argue for monarchy in robes and crowns—it proposes a Sovereign Corporation, or “SovCorp,” where the head of state is a CEO appointed by shareholders. Not citizens. Not voters. Stakeholders.

Under this system:

All public agencies are liquidated.

The bureaucracy is purged wholesale (Yarvin calls it “RAGE”: Retire All Government Employees).

The state is run for profit, with one executive holding all political power.

Citizens no longer vote. They may move jurisdictions if they’re unhappy, like customers switching service providers.

This is a monarchy updated for Silicon Valley:

No divine right. Just efficient domination.

The monarch, ideally, is not born but appointed, selected for competence, insulated from public pressure, incentivised to maintain long-term value. Think Elon Musk, but with tanks. The state, now a private entity, operates like a business: responsive only to its shareholders and immune to the volatility of public opinion.

And to keep this sovereign 'accountable,' Yarvin proposes a science-fiction twist: cryptographic kill switches. Built into the military's command infrastructure, these 'kill keys' would be held by a board of directors. If the CEO-king goes rogue, they push the button, and the guns stop firing. No revolutions, no ballots. Just backend access control. A monarch with two-factor authentication is still a monarch, just one who's read too much cyberpunk fanfiction. The 'SovCorp' is less a governance model than a LARP for men who think 'Snow Crash' was an instruction manual.

It’s laughable in its tech-utopian absurdity. But the seriousness with which he proposes it, down to the imagined encryption protocols, is part of the point. He wants this to feel buildable. Like a whitepaper, not a coup.

And in this system, what becomes of rights?

They’re obsolete.

Yarvin has no time for natural law or moral frameworks. He dismisses them as 18th-century fluff leftovers from a pre-digital world. People don’t need rights, he argues, just clear rules and competent rule. You’ll be free to do anything… except question the regime.

This is the core contradiction he never resolves:

He promises liberty in life, speech, drugs, religion, even sexual freedom—as long as you accept total political submission.

A libertarian utopia, run by an absolute king.

An Enlightenment for the code-savvy, without the burden of universal dignity.

Even the 20th century’s bloodiest lessons don’t seem to bother him. Yarvin insists that Hitler, Stalin, and Mao were aberrations, not warnings about concentrated power, but examples of bad hiring. He scorns fascism while praising Carlyle, whose 'Great Man' theory fueled Mussolini. He dismisses Hitler as a 'bad hire,' but his ideal CEO-king would wield the same unchecked power. The contradiction isn't accidental; it's insulation. His faith in the CEO-monarch is absolute. You don't ransack your own house, he likes to say, ignoring millennia of counterevidence.

This is not governance. It’s venture capital absolutism.

And the people cheering it on, the Vances, the Thiels, the anonymous technocrats who whisper about “institutional capture” aren’t fantasising. They’re planning.

Because Yarvin’s blueprint doesn’t require mass support.

It only needs buy-in from a small, powerful class who already believe the public is too dumb, too slow, and too morally confused to be trusted.

The Dark Enlightenment permits them.

To rule.

To simplify.

To stop pretending.

And Yarvin? He doesn’t care if you agree.

He’s not trying to win votes.

He’s trying to replace the operating system.

PART VI: The Critique

Curtis Yarvin insists he is not a fascist.

He hates mass politics, mocks nationalism, and openly scorns street-level racism. To him, fascism is vulgar, low-status, and emotional. He prefers his authoritarianism to be clean, clinical, and elite. A system designed like software, not shouted through a megaphone.

But the result is the same.

Strip away the branding “formalism,” “SovCorp,” “The Cathedral,” “kill keys” and what remains is a regime of total control, unchecked by law, popular consent, or moral principle. A political theology in which power is the only good, and legitimacy comes from performance, not justice.

The premise is seductive, especially for those who’ve given up on democracy. But the fantasy falls apart the moment it meets reality.

Yarvin peddles the fantasy that a sovereign ruler, chosen for competence, not charisma, would govern wisely. It’s a user manual for oligarchy, nothing more. But history is full of kings who ransacked their own house. From Nero to Leopold II to the Shah of Iran, concentrated power has never been a reliable path to long-term care. Nor has “competence” ever protected a regime from becoming paranoid, corrupt, or violently repressive.

What Yarvin offers is a CEO with nukes and no boardroom. And his only real check, encrypted kill switches held by anonymous stakeholders, is not a political safeguard. It’s a plot device from Black Mirror.

His model also depends on the idea that elites will act rationally once freed from public scrutiny. But this is fantasy dressed as realism. The American oligarchy already exists, and it doesn’t govern wisely. It evades taxes, suppresses wages, strips public goods, funds disinformation, and breaks laws with impunity. What Yarvin proposes is to make that rule official to give the shareholder class not just economic dominance, but political sovereignty.

And the people?

They become customers. Consumers of governance. Free to “exit” to another SovCorp if they don’t like the prices. Never mind that most people can’t exit poverty, let alone regimes. Never mind that citizenship becomes a subscription, and justice a product line.

He calls this post-political.

But it’s just post-accountability.

And then there’s the moral void at the centre of it all. Yarvin has no vision of human dignity. No theory of rights. No empathy for the ruled. Politics, for him, is not about negotiating competing goods or protecting the vulnerable. It’s about streamlining rules. Making society run like a well-oiled machine, even if that machine flattens people.

He treats this as tough-minded realism. But it’s not realism.

It’s designer despotism, crafted to flatter the elite and discard the rest.

Even his tone, ironic, evasive, self-amused, serves as insulation. He couches extreme positions in jest, dares critics to take him seriously, then mocks them for doing so. This is not intellectual rigour. It’s trolling with footnotes.

And yet, his ideas are no longer fringe. They’ve been laundered through think tanks, restated by senators, repackaged in Substacks and start-ups. The Yarvin worldview—that democracy is a dead religion, that competence must rule without consent, that public accountability is a flaw is now part of the American authoritarian toolkit.

The real danger isn’t that Curtis Yarvin will take power.

It’s that his ideas have already diffused through elites who don’t need to believe in kings, only in efficiency without interference.

So let’s be clear:

This isn’t a philosophical experiment.

This is a system of rules designed to suppress resistance, erase moral limits, and crown the unaccountable.

This is fascism rebranded for engineers.

A tyranny that smiles, quotes Carlyle, and promises not to be loud about it.

Curtis Yarvin is not offering clarity.

He’s offering control coded, compressed, and unchallenged.

PART VII: The Crown, the Code, and the Crowd

Closing the circuit: from Moldbug’s thought experiment to a real-world algorithm of control.

There’s something seductive about Curtis Yarvin’s vision, especially if you’re a man who feels the world has passed you by.

He offers a narrative where intelligence, not empathy, wins. Where disorder is proof that democracy has failed. Where the moral complexities of modern life can be deleted and replaced with crisp hierarchies, clean systems, and executive force. Where power is not only good, but overdue.

It flatters the alienated. Especially young men frustrated, disillusioned, clever enough to distrust mass politics but not grounded enough to imagine alternatives that don’t end in domination. The Yarvin worldview tells them they’re right to feel betrayed. That liberalism is a scam. That history is a lie. That weakness wears the mask of equality.

It’s a system built for men who want to rule without asking for permission or at least to believe that someone like them could.

And right now, that system is on the rise.

We live in a moment where the mechanisms of democracy are visibly faltering, courts ignored, votes discarded, strongmen returned to power with smirks. In 2024, Donald Trump tweeted, “I am your retribution,” later retweeting the Napoleon quote “I am the state”, and mused aloud that being president made him “like a king.” His allies in the next administration—including J.D. Vance and others who’ve openly praised Yarvin—aren’t planning to govern. They’re planning to dismantle.

And in that vacuum, the Dark Enlightenment becomes more than a blog or a meme. It becomes a permission structure for the authoritarian turn. A rationalisation for discarding rights, dismantling institutions, and concentrating power in the hands of “the capable.” Which is to say: the rich, the connected, and the self-anointed “smartest guys in the room.”

For everyone else, there is no role.

The red-pilled believe they’ve seen the truth.

The black-pilled have given up on resistance.

And in the space between, a new order takes shape, marketed as efficiency, delivered as exclusion.

What happens to those who don’t pass the test of merit or wealth in Yarvin’s world?

They don’t get a vote.

They don’t get a voice.

They get algorithmically managed, or priced out, or moved along.

Maybe, if they’re lucky, they get to donate their organs to someone higher up the stack.

This isn’t theory anymore.

It’s metastasising.

Not in the language of jackboots or military parades—but in Substack essays, crypto-ledgers, startup boards, and legal theories about a “unitary executive.” In the quiet elimination of dissent under the guise of “order.” In billionaires who speak like kings, and foot soldiers who believe submission is strength.

And at the centre of this is a man who sees himself as a designer of regimes. Not a politician. Not a pundit. A coder of power.

Curtis Yarvin didn’t start a movement. He wrote a user manual for the next American oligarchy, and a generation of men is already following its instructions

The damage is already done. The only question is who will inherit the blueprint—and how far they're willing to take it. Yarvin's crown jewel isn't his ideology. It's his rebranding of authoritarianism as a 'glitch fix' for democracy. The danger isn't that we'll wake up to a CEO-king. It's that we'll shrug as the tools to build him are normalised by men who quote Moldbug between TED Talks and budget meetings.

Great article!!!!...Ahhh!!!, Yes, Curtis Yarvin, the infamous "Systems Architect", who opportunistically exploited the extremely high 'Probability of Ruin' theory in How-To Dismantle a massively over-indebted political and social system backed by the Federal Reserve Act 1913, aka so-called Govopoly System.

History shows us that when the Global Order snowballs into decline because it is unable to meet its debt obligations, the monetary, political, and social systems are vulnerable to theft.

IMHO, The SovCorp or The Govopoly System has always been in operating in plain sight in America (especially since the 20th Century), but because "extremism" has (re)surfaced or normalized in more recent times due to a shift in the Global Order, and as a result, the veil or curtain has been pulled back for those aware enough to see the scam or fraud that is the "American Democratic System".

In response to the nonsense Yarvin has spouted for many years, my simple retort for his delusional mind is: If the kernel (core) of any operating system is susceptible to any bugs or errors, then the operating system controlling all the systems will be riddled with bugs and error-prone. The irony is that Yarvin, just like Thiel and Musk, are all so unintelligent that they are unable to recognize that their ruling systems are full of flaws, bugs and errors